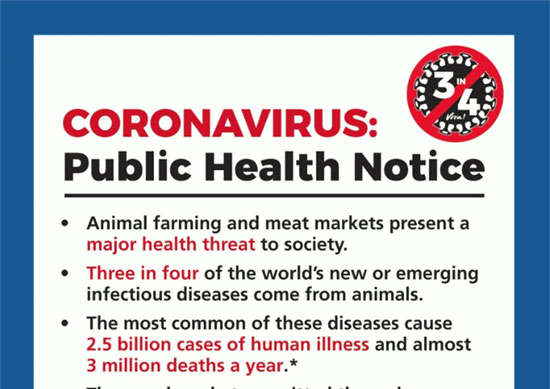

Zoonotic diseases – 3 in 4

Zoonotic diseases are appearing with increasing frequency. Swine flu and Covid-19 emerged in recent years, others that have emerged over past decades include SARS, MERS, Ebola and HIV – they all came from animals. The Covid-19 pandemic is the worst we have seen for generations. It is a warning of things to come if we don’t change the way we treat animals; as we continue to encroach on wildlife and expand factory farming, the threat of another pandemic increases.

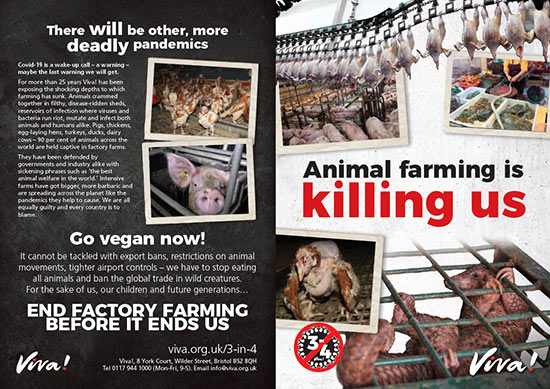

The next pandemic could be caused by a highly pathogenic bird flu virus with the potential to kill 60 per cent of those infected. Larger than any terrorist threat! It might be an antibiotic-resistant superbug that runs riot. It could be a new monkeypox variant or a completely new, previously unseen virus. It might be the resurgence of an old pathogen. It’s time to make the connections between eating meat and the destruction of wildlife, antibiotic resistance and disease outbreak. It’s time to end factory farming and go vegan.

You may not have heard the word ‘zoonotic’ until recently, it sounds rather exotic! But did you know that measles, whooping cough, tetanus, polio, HIV and the seasonal flu that circulates every winter all came from animals? Recent infectious disease outbreaks such as SARS, MERS, Covid-19 and monkeypox are just a few more in a long line of zoonotic diseases but what concerns scientists is that they are now emerging with increasing frequency.

Find out more about zoonotic diseases and how we can stop them

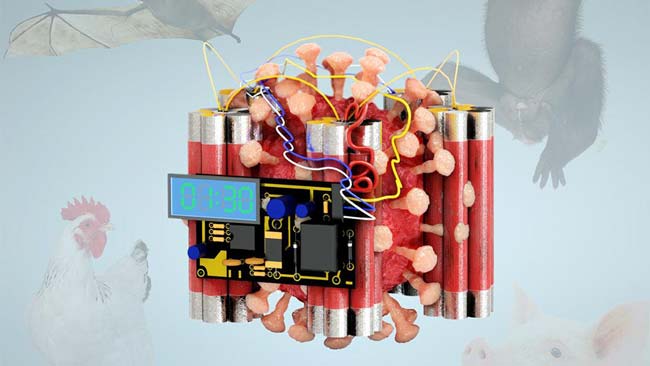

Zoonoses: a ticking time bomb

Read our report on emerging diseases originating in animals and their impact on humanity.

Big City Radio

Juliet joins Big City Radio to talk about our open letter recently posted in The Independent and our 3 in 4 campaign.

The Independent

If more of us were vegan, there would be less chance of a pandemic in the future

Daily Mail

Animal welfare campaigners urge public to go VEGAN to protect against future pandemics — claiming factory farms and wildlife markets provide the perfect conditions for disease to thrive

We’re asking for your help in sharing our message. Post either a photograph of your hand or a paper note with #3in4 written on it to your social media pages.

In your post you can include the text:

Three in four new or emerging infectious diseases come from animals and factory farming is a ticking time bomb for future pandemics. The time to end factory farming and choose vegan is now.