The physiology of a vegan

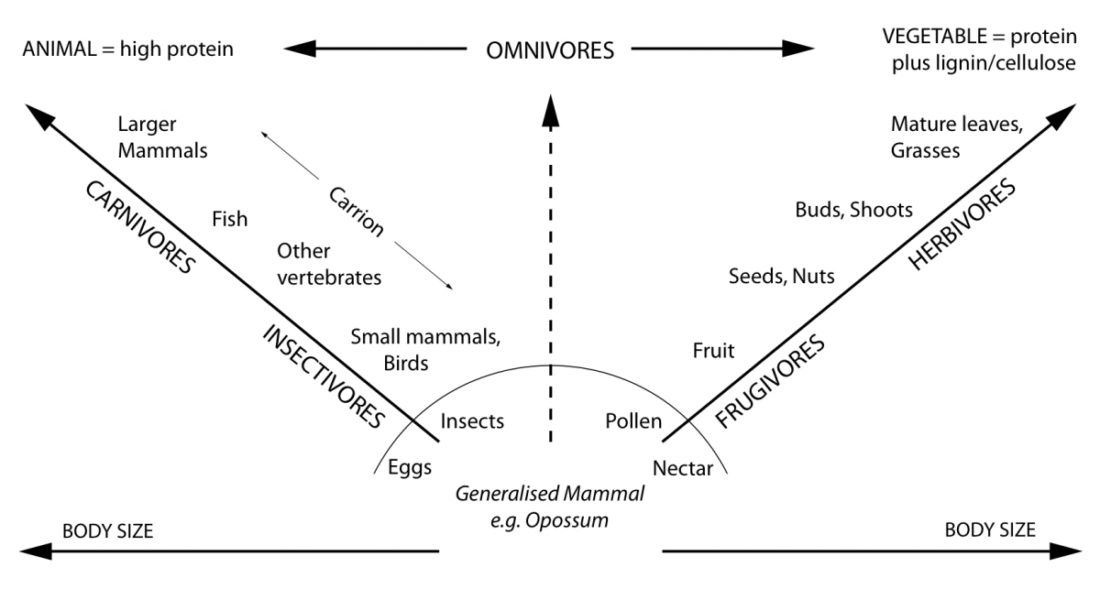

One of the most pervasive myths surrounding veganism is the belief that humans are naturally meant to eat meat – that we are evolutionarily adapted to eat and thrive on dead flesh. The evidence presented in these pages knocks this myth firmly on its head. Human beings belong to the primate family and the primate family is essentially a vegetarian one. Our closest living relatives such as chimpanzees and gorillas live on a diet of foods overwhelmingly derived from plants, and we ignore our evolutionary past at our peril. Indeed we are already seeing the dangers of dismissing what evolutionary studies show us we should be eating – plants, not animals – with the growing epidemics of killer diseases such as cancer, heart disease, obesity and diabetes which are now occurring in almost every corner of the planet.

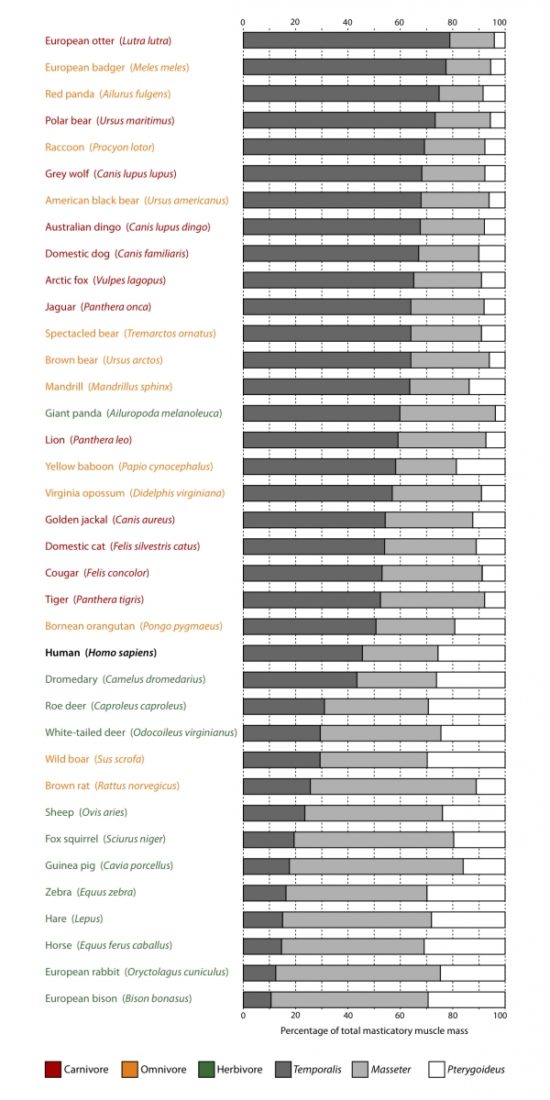

Compare human physiology to carnivores, omnivores and herbivores in the table below and then click on the headings beneath the table to explore in more detail.

| Physiology | Carnivore | Omnivore | Herbivore | Human |

|---|---|---|---|---|

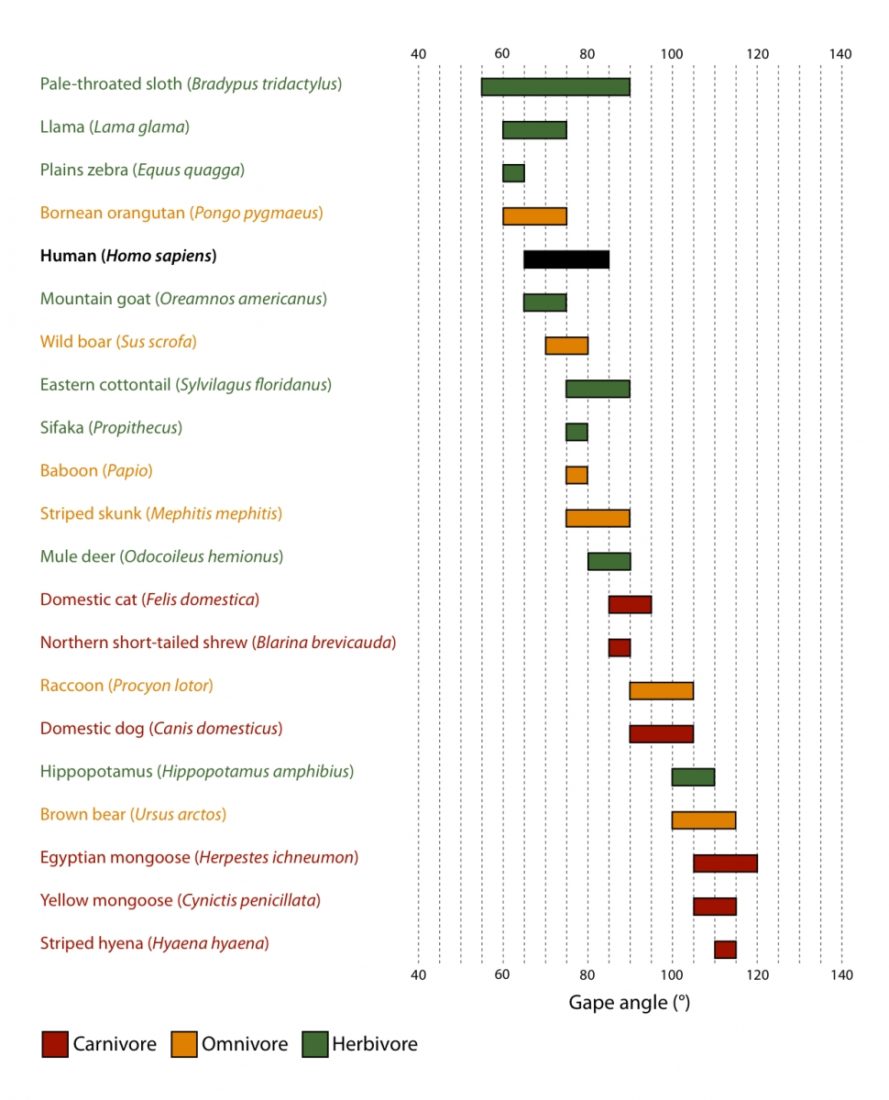

| Cheek muscles (Herring and Herring, 1974; Fehrenbach and Herring, 2013) | Reduced to allow wide mouth gape | Reduced to allow wide mouth gape | Well-developed to aid chewing | Well-developed to aid chewing |

| Jaw motion (Schwenk, 2000; Feldhamer, 2007) | Slicing; minimal side-to-side motion | Slicing; minimal side-to-side motion | No slicing; good side-to-side, front-to-back motion | No slicing; good side-to-side, front-to-back motion |

| Mouth opening vs head size (Herring and Herring, 1974) | Large | Large | Small | Small |

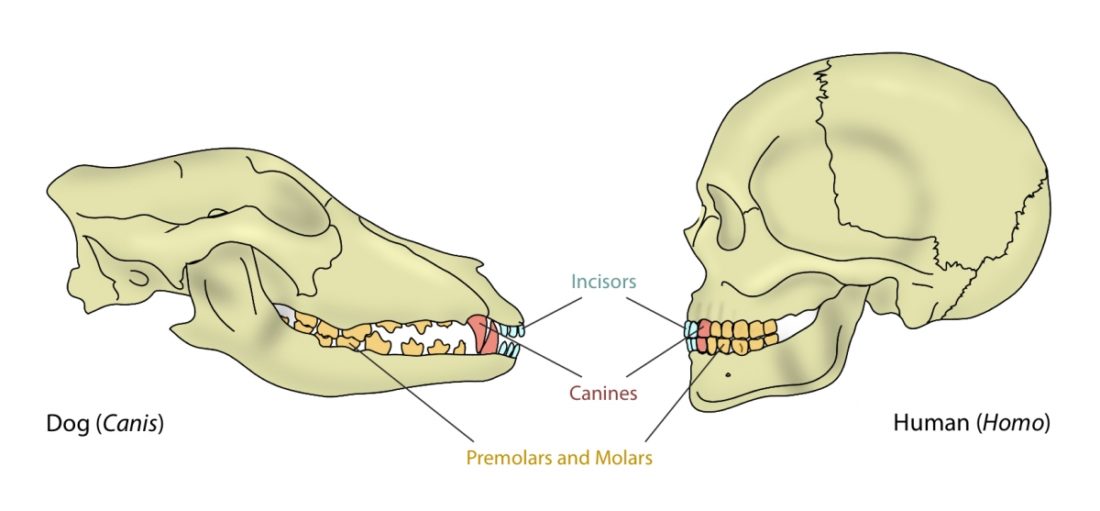

| Teeth: incisors (front teeth) (Hillson, 2005; Feldhamer, 2007) | Short and pointed | Short and pointed | Broad, flattened and spade-like | Broad, flattened and spade-like |

| Teeth: canines (Hillson, 2005) | Long, sharp and curved | Long, sharp and curved | Dull and short or long (for defence), or none | Short and blunted |

| Teeth: molars (back teeth) (Ungar, 2015) | Sharp, jagged, and blade-shaped | Sharp blades and/or flattened | Flattened to crush and grind food | Flattened to crush and grind food |

| Chewing (Ungar, 2015) | Hardly any; swallows food whole | Hardly any or simple crushing | Extensive chewing necessary | Extensive chewing necessary |

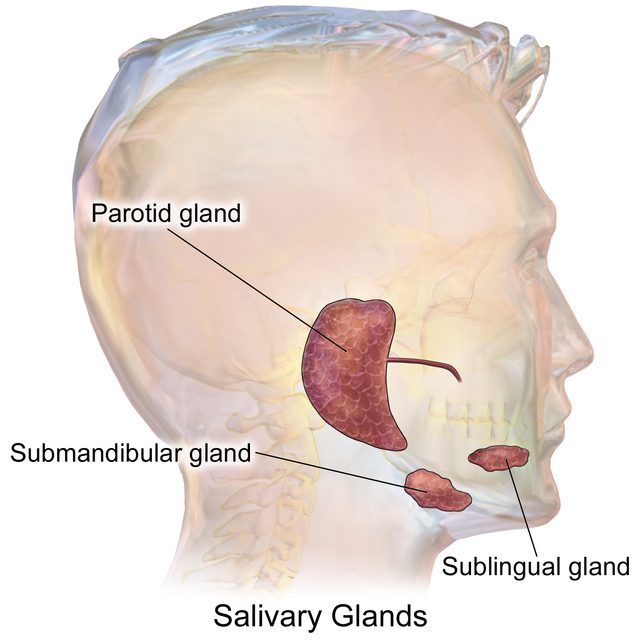

| Saliva (Tucker and Miletich, 2010; Boehlke et al., 2015) | Mostly mucous saliva, not large volume No enzyme amylase to pre-digest carbohydrates | Seromucous (mixed) saliva Amylase in the saliva to start carbohydrate digestion | Mostly serous (watery) saliva, larger volume Alkaline saliva; amylase to start carbohydrate digestion | Mostly serous (watery) saliva, larger volume Alkaline saliva; amylase to start carbohydrate digestion |

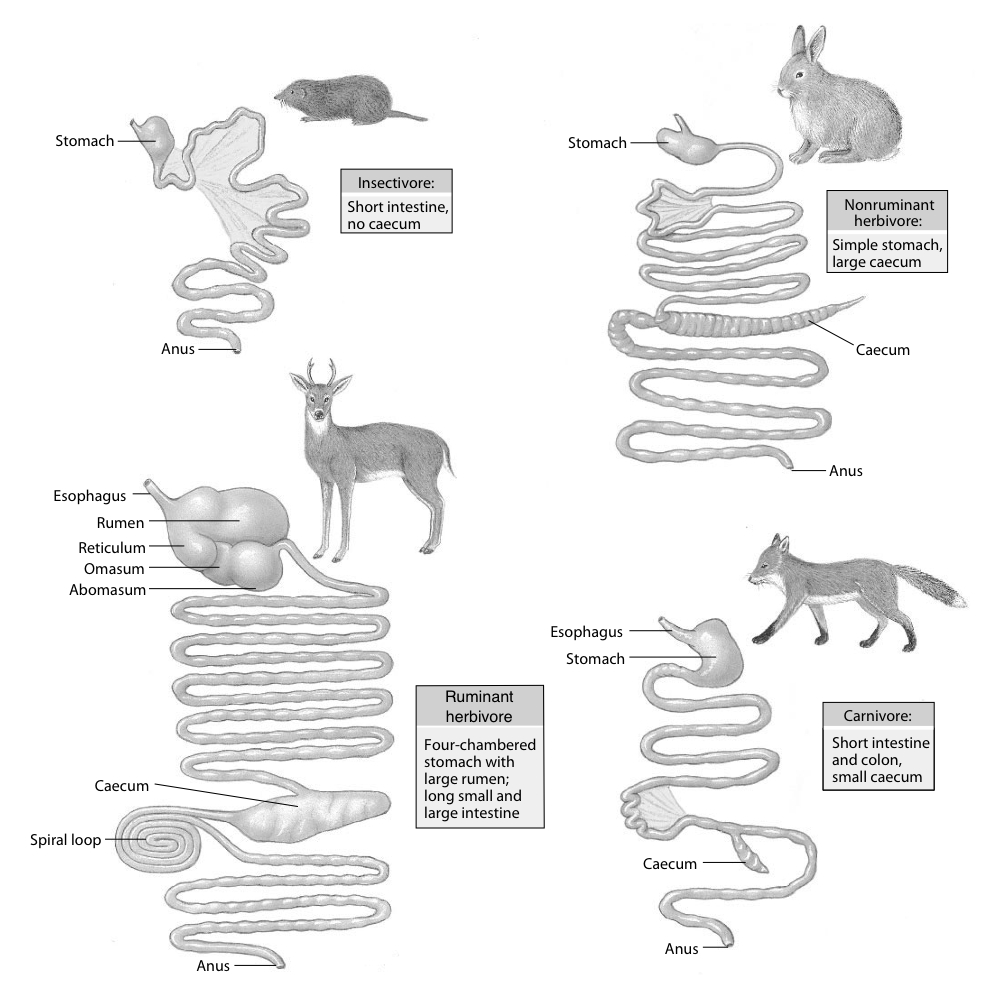

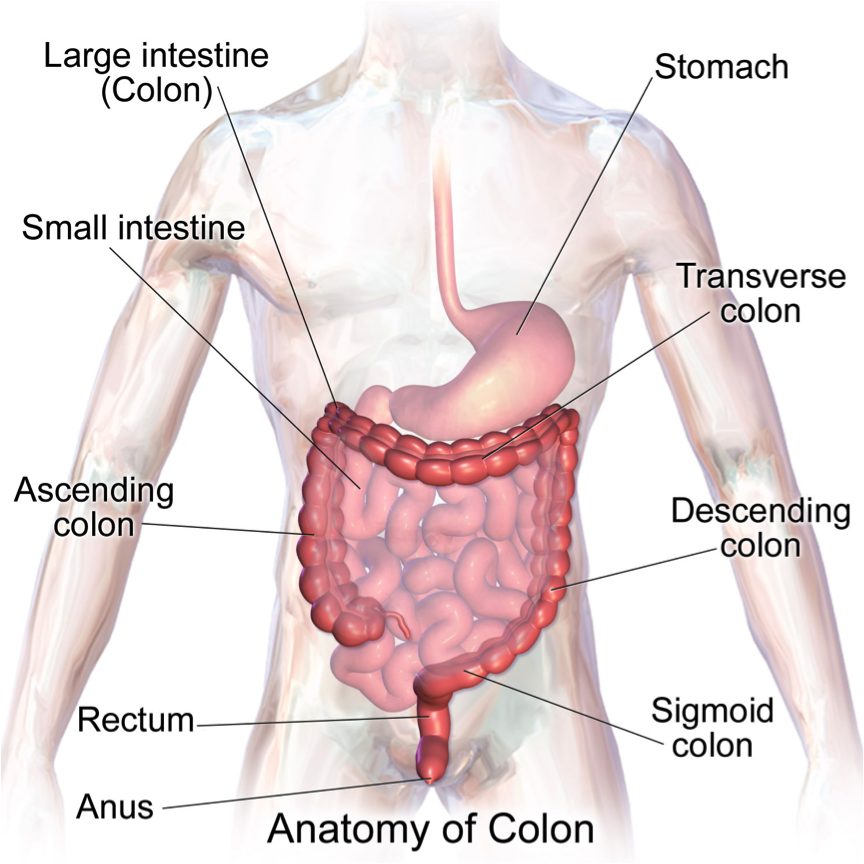

| Colon (Kararli, 1995) | Simple, short, smooth | Varied | Long, complex, often sacculated | Long and sacculated |

| Nails | Claws | Claws or sharp hooves | Hooves or soft nails | Soft nails |

| Body cooling technique (Willmer et al., 2009) | Panting | Panting | Sweating | Sweating |

Carnivores mainly or exclusively live on a diet of animal tissue. They can be predators or scavengers or both. Herbivores mainly or exclusively eat plant matter. Omnivores eat both.

Humans (Homo sapiens) are certainly capable of consuming both animal and plant foods. Whether we are morphologically and physiologically more adapted to consume one or the other, however, is something we will explore here. See for yourself whether we have more traits in common with carnivores, omnivores, or herbivores.

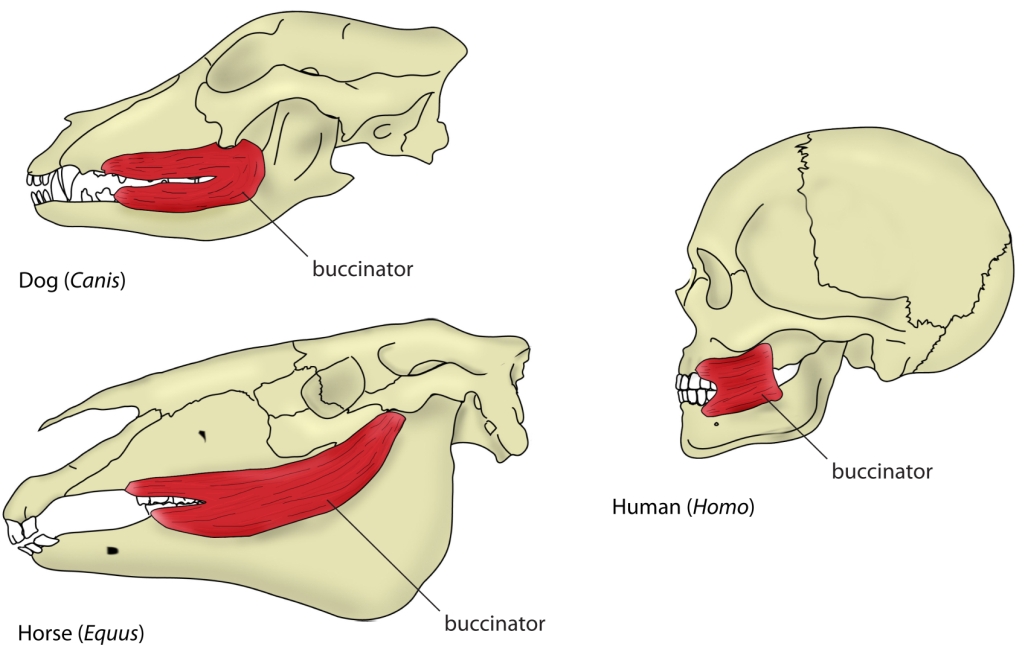

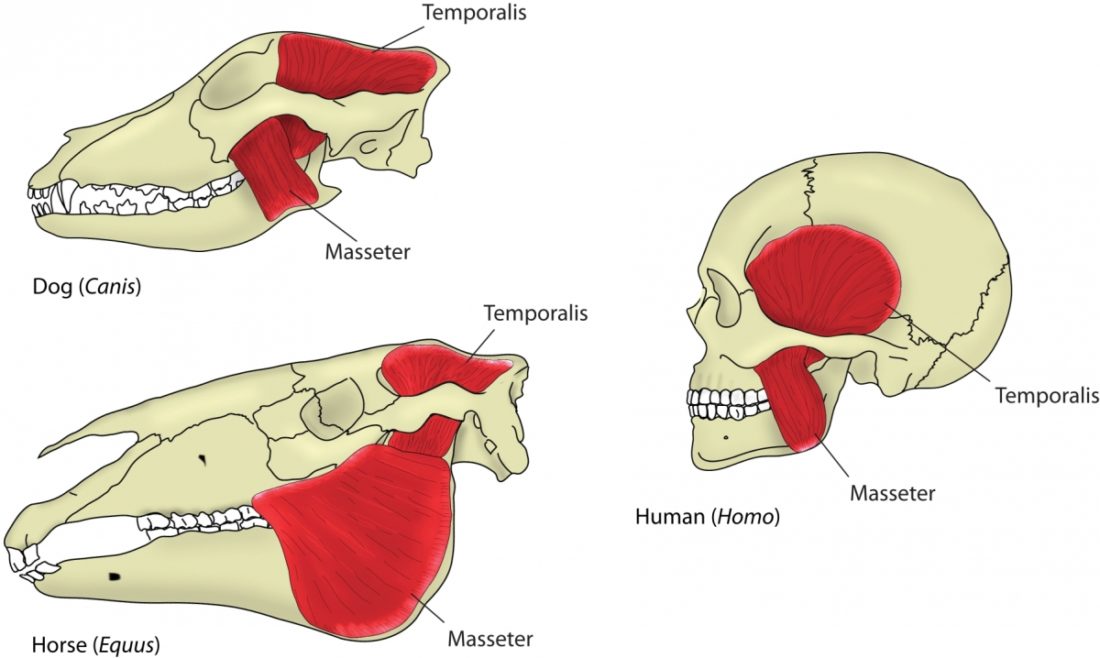

The mouth opening, or gape, in mammals serves a variety of purposes: breathing, vocalisation, prehension of food, but also agonistic display. The mammalian jaw system has adapted to each species’ behaviour and diet. All mammals have in common that the frontal, prehensile part of the jaw is covered by the lips and the premolar and molar teeth (used for chopping up and chewing food) are covered by the cheeks. The cheek muscle, musculus buccinator (Fig. 1), assists the tongue in placing and keeping food where it needs to be while we chew.1Fehrenbach, Margaret J., and Susan W. Herring. Illustrated anatomy of the head and neck. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013.

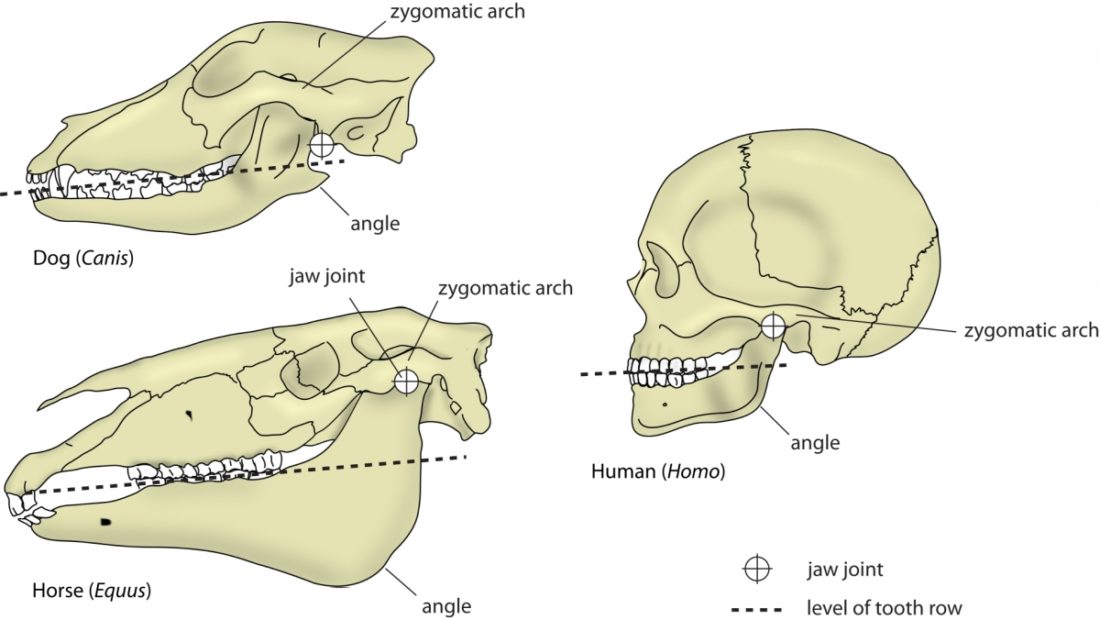

A distinguishing feature between carnivores and herbivores is the posterior end of the jaw, the so-called angle (Fig. 1). It is the boney bit you can feel just below your ears. In carnivores and most omnivores, the angle is quite small. In herbivores and humans, it is expanded and convex.

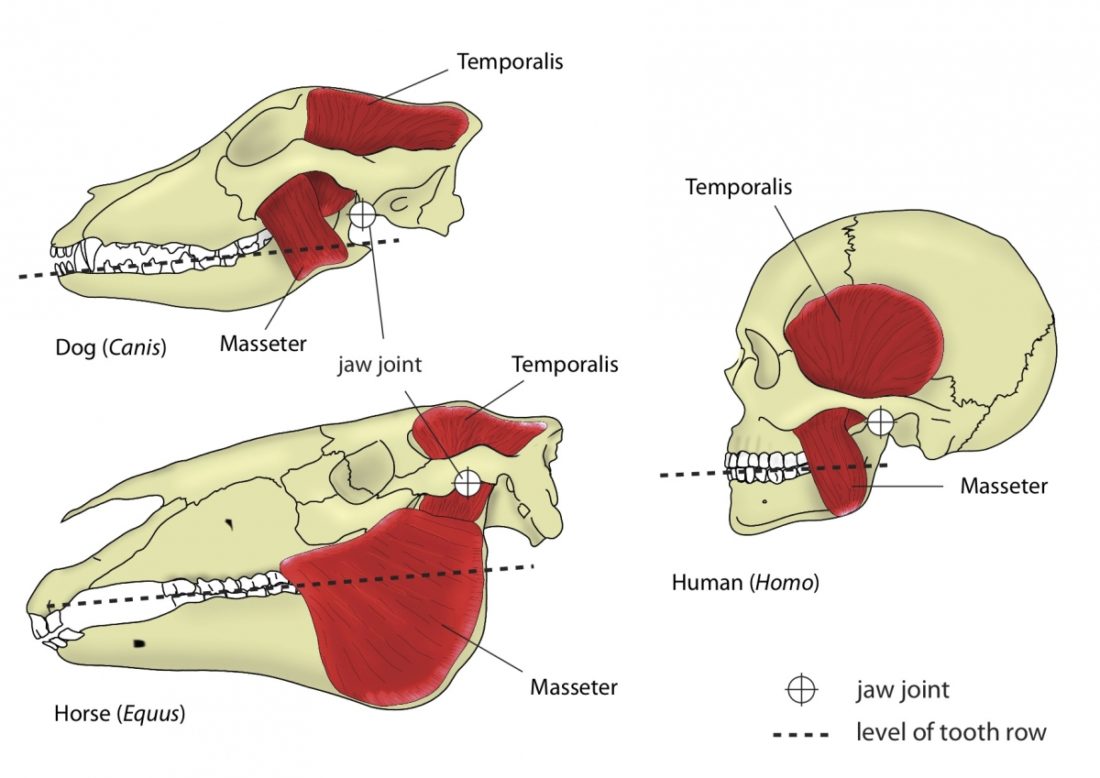

Most carnivores are predators who hunt, kill, and butcher their prey.1Feldhamer, George A. Mammalogy: adaptation, diversity, ecology. JHU Press, 2007. These predators kill either with a single, strong penetrating bite (e.g., mustelids and felids) or several more shallow bites (e.g., canids and hyaenids). Due to the morphology of their jaws and adductors (Fig. 1), they bite with a chopping (up and down) motion. Their jaw joint is on the same level as the tooth row, which allows for a scissor-like jaw motion, but makes horizontal movement (side to side, backwards and forwards) impossible.2Schwenk, Kurt. Feeding: form, function and evolution in tetrapod vertebrates. Academic Press, 2000.

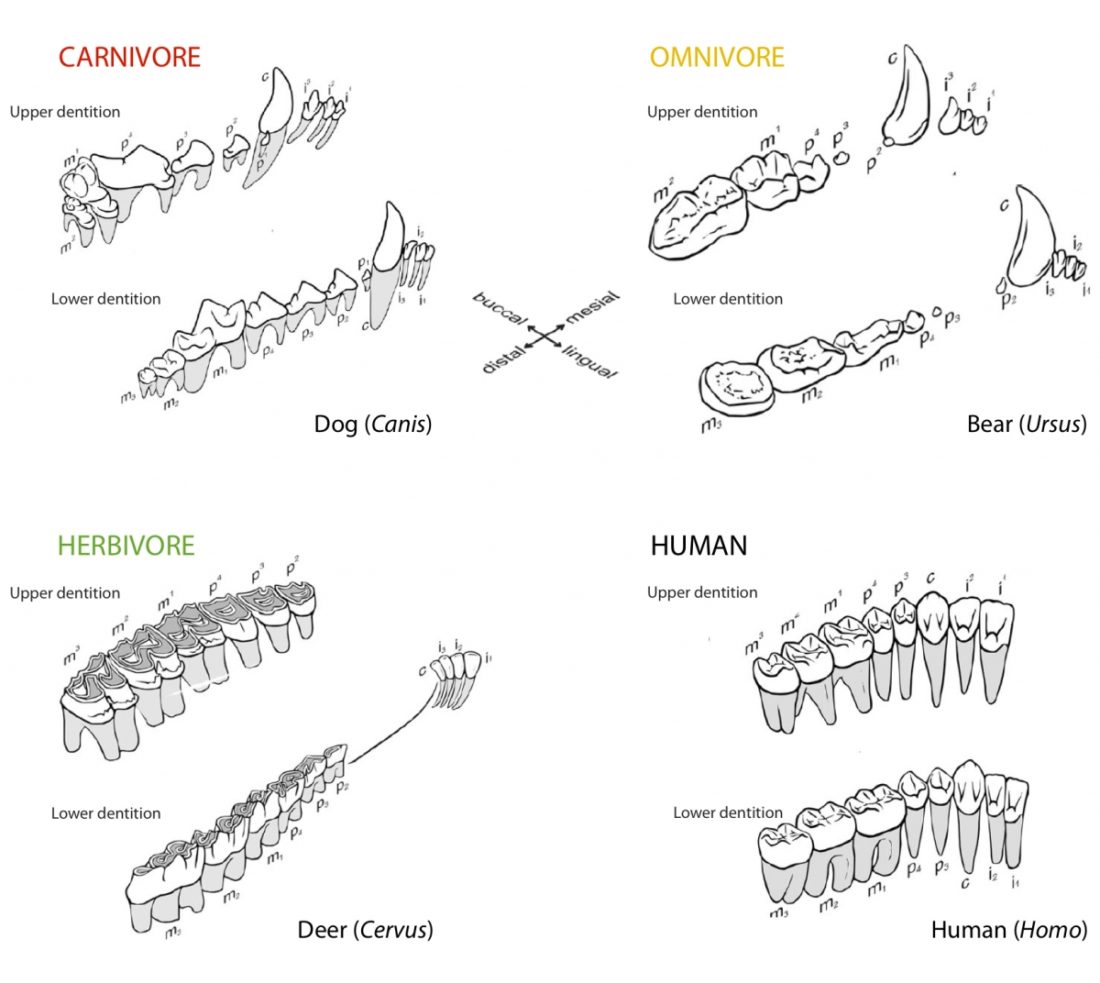

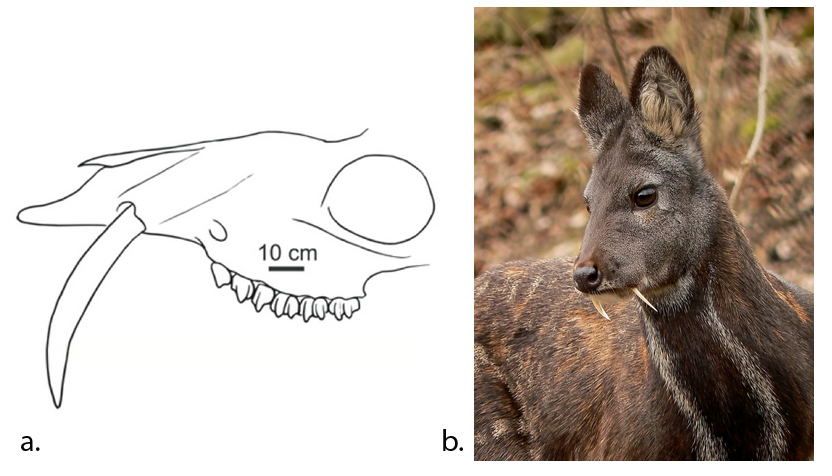

One of the most distinguishing features between mammals with different diets are their teeth (Fig. 1). The dentition of a species has adapted to process a particular, preferred diet.

Different dietary habits of mammalian groups are reflected in the size and importance of the three major salivary glands (the parotid, sublingual, and submandibular glands1Tucker, Abigail S., and Isabelle Miletich, eds. Salivary glands: development, adaptations and disease. Vol. 14. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers, 2010. (Fig. 1) and the viscosity of the saliva they produce.

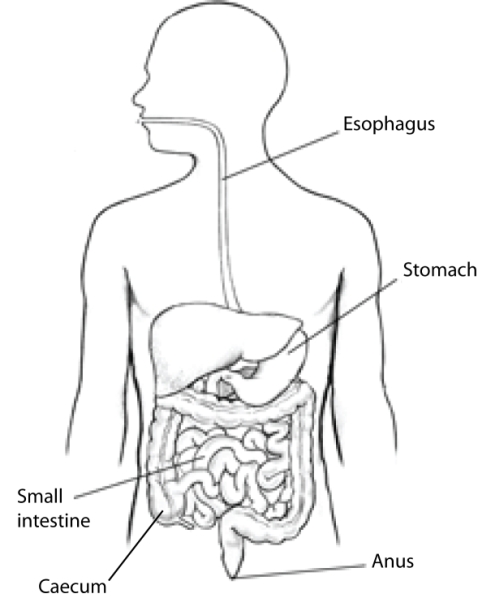

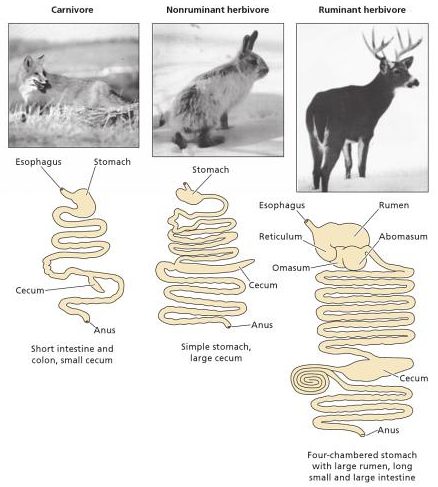

The morphology of mammals’ digestive tracts reflects their evolutionary adaption to different diets (Fig. 1). The digestive tract of herbivorous mammals is generally much longer than that of carnivores.1Linzey, Donald W. Vertebrate Biology. McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math, 2000. The increased length – especially of the small intestine – allows for more time for the cellulose of plant cell walls to be broken down by microorganisms.

The role of diet in colon morphology becomes clear when considering that even within the same order of mammals, differences can occur. Such is the case within the order of primates: more carnivorous primates have simple and smooth-walled colons, while frugivorous primates have an elongated, sacculated colon.1Chivers, David J., and Claude Marcel Hladik. “Morphology of the gastrointestinal tract in primates: comparisons with other mammals in relation to diet.” Journal of Morphology 166.3 (1980): 337–386.

Most mammals regulate their body temperature through evaporative heat loss. There are two main methods of doing this: sweating and panting. Whereas most herbivores have sweat glands spread out over the body surface, sweating being their predominant body cooling technique, nearly all carnivores lack these glands and pant in order to cool down (Fig. 1).1Willmer, Pat, Graham Stone, and Ian Johnston. Environmental Physiology of Animals. John Wiley & Sons. 2009.